This is a living project.

Objective: Attempt to build a new additive manufacturing method.

Reason: It’s an interesting and multidisciplinary project.

Challenges: Repeatability within the process.

Results so far: I have deposited material onto a substrate and selectively sintered it using a 50W fiber laser, achieving similar results to powder bed fusion.

Below I document progress, results, learnings, and assumptions that have been challenged.

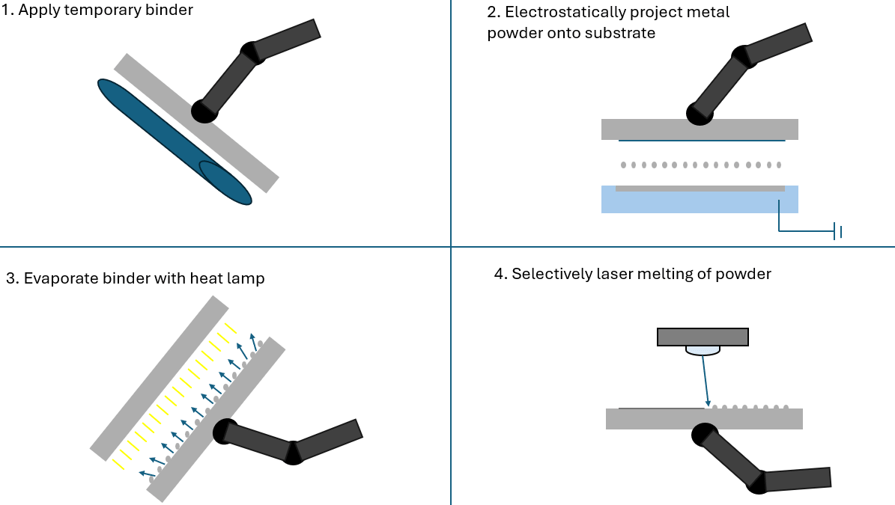

Process Chart

General Project Commentary

Below is a commentary I made of the project where I briefly walk through components in the printing system. To learn more, continue scrolling down after watching the video.

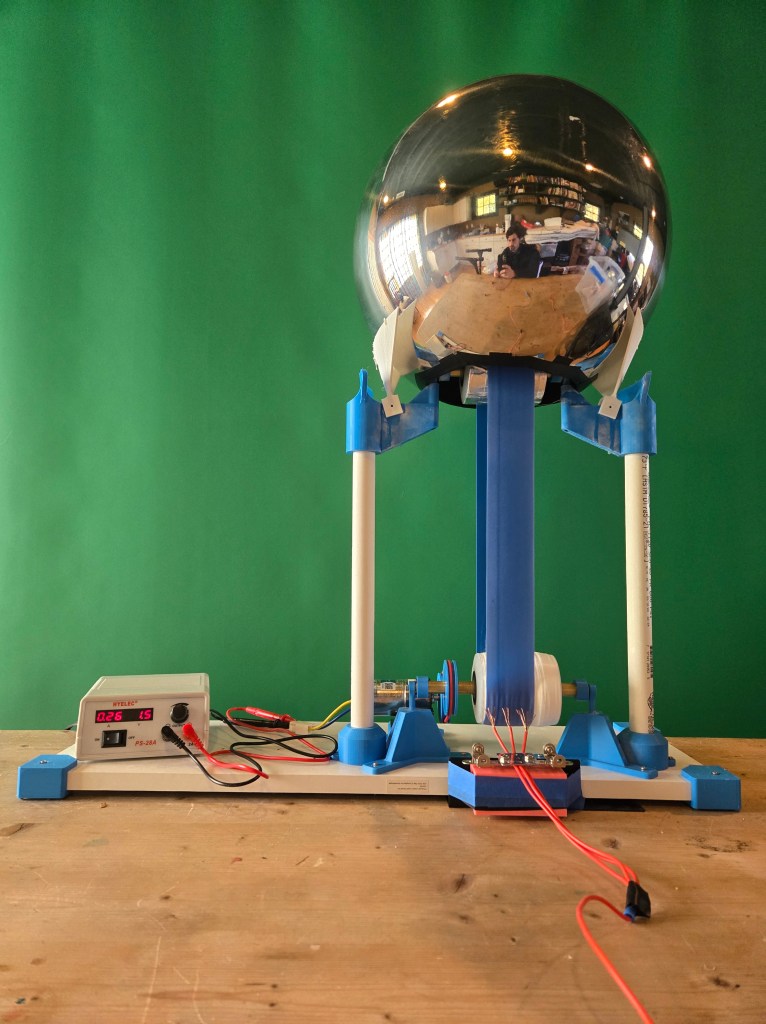

The Electrostatic Generator – Just like in your high school science class

This Van de Graaf (VDG) generator is used to generate an electrostatic charge which is used in the 3D printing process as the material deposition modality. It runs on a 12V 600RPM electric motor.

The thing about VDG generators is that they are conceptually very simple, and operationally even more simple. However, their finicky nature seemingly scales with their simplicity. Building this thing to reliably work took more effort than I expected. The result, though, is a plug and play VDG which always works 9 times out of 10.

Here is a video demonstrating the static effect.

Observations From the Process

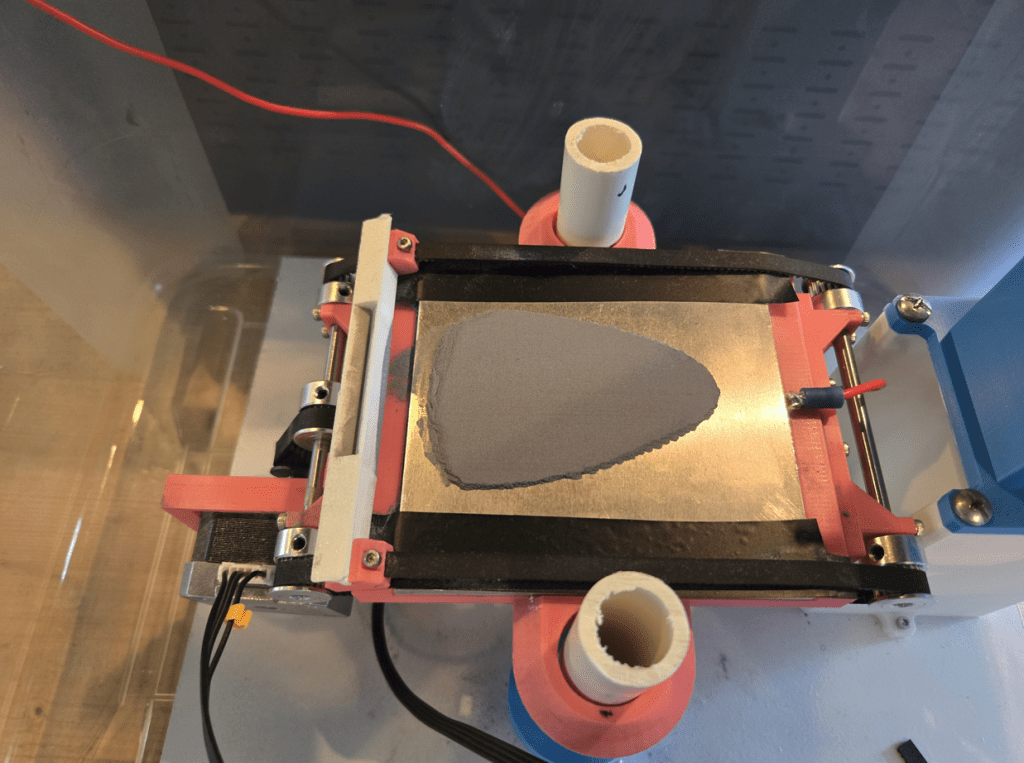

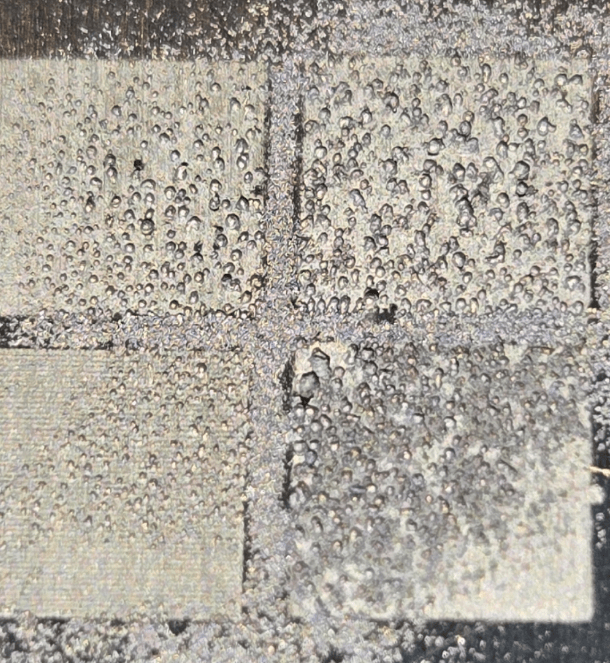

Image showing the powder bed on the electrostatically charged plate.

Image showing material after electrostatic deposition onto the substrate.

Hmm, the material on the right looks a little sparce compared to the powder bed on the left. This was an interesting observation, and what I learned was that in order to have a complete deposition across the entire face of the substrate, the powder bed itself needed to be larger than substrates face. This was not happening with the arrangement of plates that I had, but this is proven in the image below with some random objects. I never performed the sintering step on these parts, but they just serve to illustrate the fact that in order to get a fuller deposition of material, the substrate/build plate needs to be smaller than the powder bed. In the above case, the substrate was larger than the powder bed leading to unwieldy and unpredictable electrostatic depositions. Layer heights were measured to be about 80 microns, which is in the operating range of similar laser powder bed fusion technology which has an ideal layer thickness around 60 microns, but a range roughly from 30 to 250 microns (with significant porosity occurring at thicker layer levels).

Seeing the Machine in Action

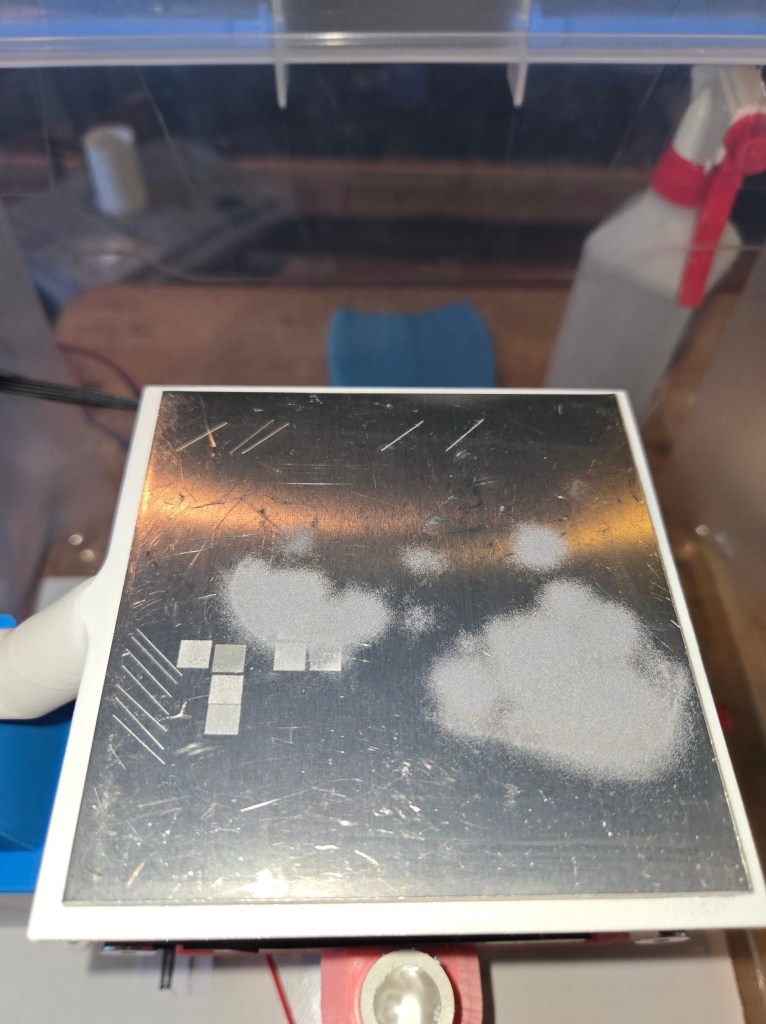

Results After Laser Scanning

The image below shows sintered material inside of the powder layer and after depowdering. The deposited material is stuck onto the substrate, however, it is quite “fluffy”. I suspect this for two reasons, first is that it is being sintered onto an unheated build plate, so as it is being sintered there is simultaneously a rapid loss of heat to the bulk mass of metal below it which could cause a strange melt phenomenon. But I think the main reason is that in this case I was experimenting with the laser focus, and in this case the laser had a broader spot size, so its possible the energy density was not enough to cleanly melt the metal powder into clean tracks.

The size of the circles seen above are about half the diameter of a penny.

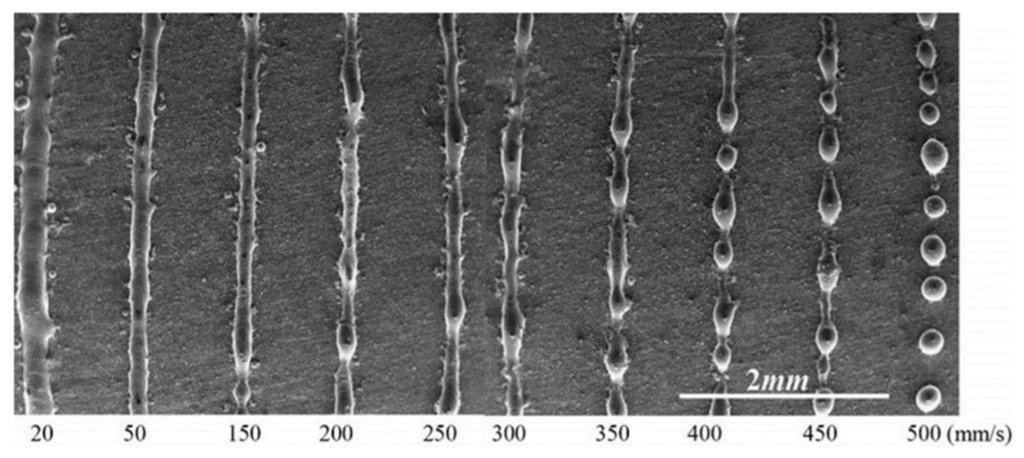

Balling

A really cool thing to notice is that when comparing the two images above, we can see that they are quite similar to some results seen in laser powder bed fusion shown below. This makes sense because these processes fundamentally are the same in their binding modality, its just that they differ in the material deposition modality:

Lines – Finally

After continuous adjustment of some parameters, I was able to get some lines and improve from the balling.

Discussion of the Results

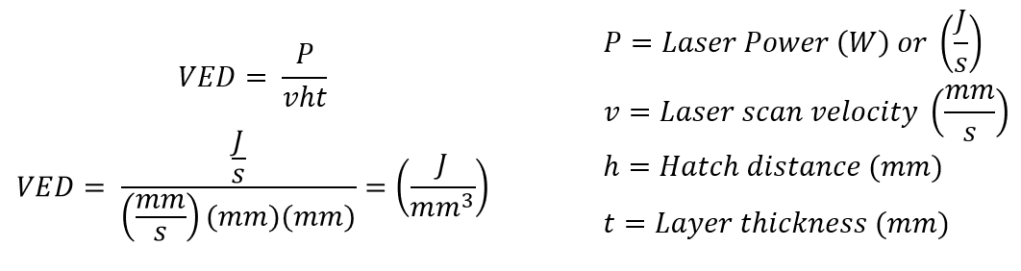

Laser energy density plays a critical role in the process of melting powder to a substrate. It is measured in its volumetric form by the following equation:

So volumetric energy density is one parameter of many that is needed to get right in a metal powder process, and it is defined by 4 other individual parameters. If you consider aluminum for a moment, it has an ideal energy density of roughly 60 J/mm^3 for laser powder bed fusion. However, with those 4 parameters listed above alone, there are about a million different ways to get to that 60 J/mm^3. Should I use a really slow scan speed and a really low laser power? How will that work with the layer thickness? If the hatch distance is too close or too far, what will that do to surrounding powder? If I change this parameter, how will I need to change that other parameter? That’s not even mentioning things like the laser beam profile or powder bed temperature.

I think you might get the point now of just how delicate and complicated this process can become. Determining the ideal operating characteristics of the process is a process in and of itself, one that requires great deals of trial and error. And time, lots of time.

This is also why this is a living project. It takes a lot of time to figure these things out.

Considering the images above, though, I achieved results similar to the laser powder bed fusion, which is currently the leading metal AM technology. As a lone investigator of this methodology, I think I have developed some very interesting results.

Challenges

- Laser focusing and beam shaping

- keyholing and underpowered laser (keyholing is melting of powder and substrate underneath for full fusion of a layer

- Lack of repeatability in the process with current state of the DIY setup

- Poor layer surface quality is due to the rapid cooling of the powder onto an unheated plate as well as the mostly unideal laser beam profile

How Would I Improve This?

To further improve on this, I think better process control is a must. Frankly, a DIY setup does not offer sufficient repeatability to investigate the relationship between the parameters involved in this project to make any determination on process viability. Even when you consider laser powder bed fusion (being the closest technology to this process I have developed) it still suffers from some repeatability challenges.

But how would I implement some of these improvements if money was not a consideration?

- High repeatability (in the realm of 10 micron) 6-axis robotic arm used to cycle the substrate between stations

- I would use high-accuracy limit switches to control the positioning of the robotic arm as it approaches the lasering station, to ensure that the laser beam is always focused at the vertical offset as well as ensuring consistency on the X and Y offsets.

- I would build a much better inert chamber and use oxygen sensors to monitor the oxygen levels

- I would also use a higher power laser for better keyholing effects between the metal powder and the substrate